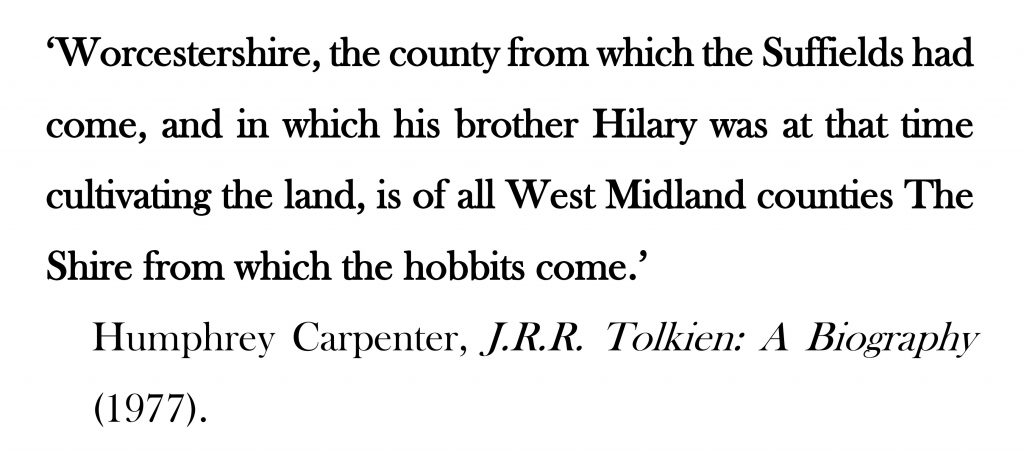

As scholars of Tolkien’s work have documented, places and events from his life occasionally found their way into his fiction. What is less appreciated is the degree to which some of the names and geographical details of the Shire echo (deliberately or not) those of the West Midlands. Take the map of ‘A Part of the Shire’ that you will find in any copy of The Fellowship of the Ring, for example:

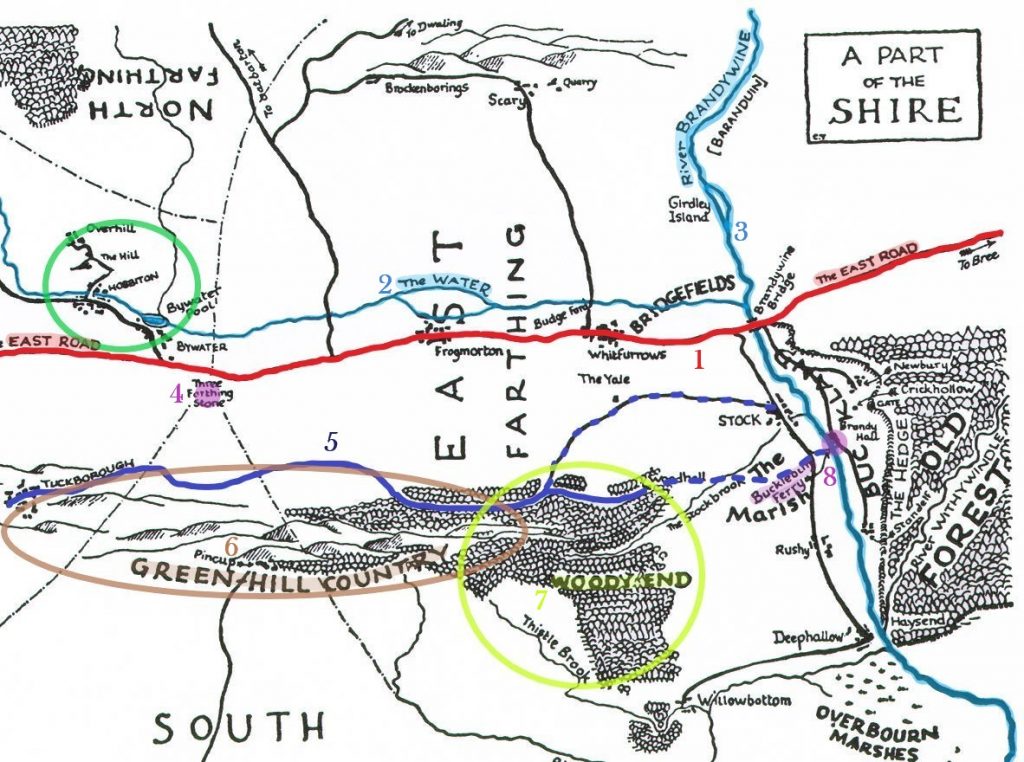

If one turns a map of the real landscape of the West Midlands through ninety degrees and highlights the two most important ancient roads, there emerge some similarities with the fictional Shire landscape:

- In the Shire, the East-West Road [which I have marked as ‘1’ on the map of the Shire] is reminiscent of the partially lost road in the Midlands known as Icknield Street. The latter ran in a north-south orientation past some important landmarks of Tolkien’s youth, including the four Edgbaston houses in which Tolkien lived between 1902 and 1911.

- The East-West Road runs parallel to a stream called The Water [2], which joins the larger River Brandywine [3]. Icknield Street ran beside the Rivers Rea and Arrow to where the latter meets the larger River Avon. The word ‘Avon’ stems from the Brittonic word abona, meaning ‘river’. Thus the names ‘Brandywine’ and ‘River Avon’ are similarly made up of two words which have roughly the same meaning.

- The East-West Road crosses the Brandywine over the Bridge of Stone Bows, relatively near a place called Budgeford in Bridgefields. Icknield Street crossed the River Avon at Bidford-on-Avon, where there is still a medieval stone bridge with seven arches.

- On the east bank of the Brandywine lies a territory called Buckland and a settlement called Bucklebury. On the south side of the Avon, where Tolkien’s brother Hilary lived, Icknield Street is also known as Buckle Street.

Furthermore, various locations on the East-West Road may be related to real places that lie along the route of Icknield Street:

- Bywater, a village above a ‘wide, grey pool’, bears some resemblance to Edgbaston.

- Hobbiton, the settlement in which the Baggins family have long resided, is situated on the slopes of a hill across the valley from Bywater. Between the 1870s and 1910s, Tolkien’s maternal family, the Suffields, were concentrated around the hill at Moseley, on the other side of the River Rea from Edgbaston. Tolkien himself lived in this general vicinity from 1895 to 1902.

- Between the villages of Bywater and Hobbiton is the Old Mill. Until the 1960s, Avern’s Mill stood beside the River Rea on the road between Edgbaston and Moseley. Its existence was first recorded in 1231.

- The distance between Hobbiton and the Brandywine Bridge is forty miles. It is twenty miles (as the crow flies) from Moseley to Bidford-on-Avon. However, given we are told that Hobbits are ‘about half our height’ or ‘between two and four feet of our measure’, Tolkien may originally have intended Hobbit ‘miles’ to be half as long as our own.

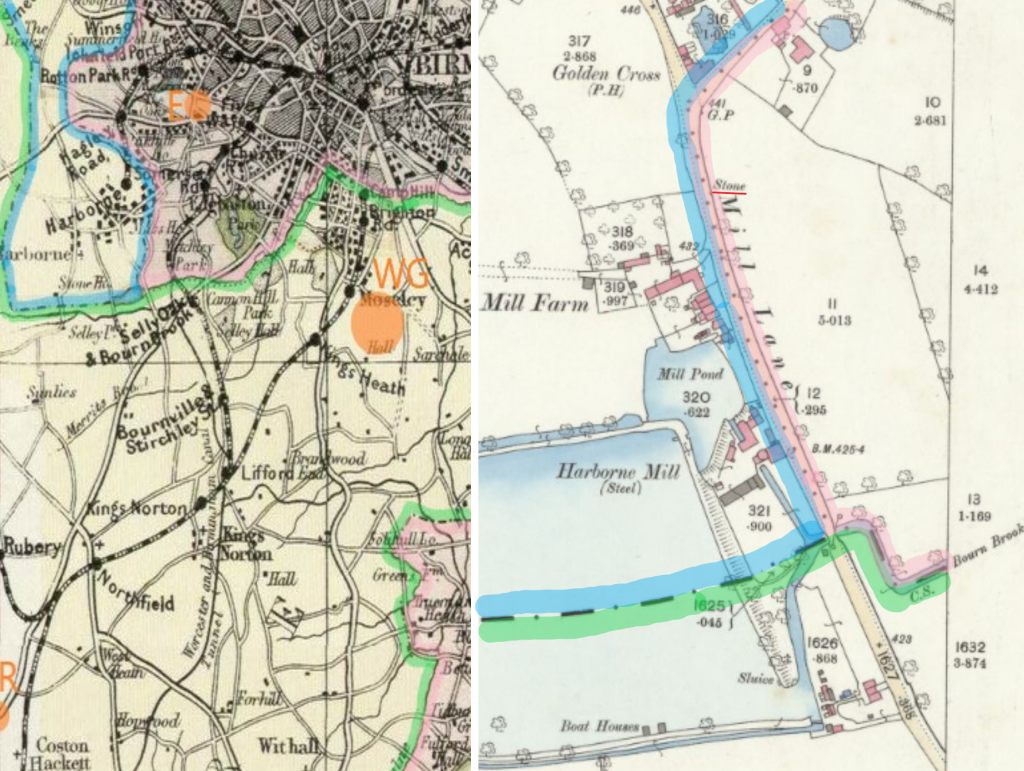

- A short distance south-east of the East-West Road at Bywater stands the Three Farthing Stone [4]. This marks the centre of the Shire and the meeting point of three of its quarters. At a similar spot relative to Edgbaston and Icknield Street, where Harborne Lane crosses the Bourn Brook at Monks’ Bridge, exists the erstwhile juncture of the counties of Staffordshire, Warwickshire and Worcestershire. Although no ancient boundary marker is obviously present today, Ordnance Survey maps published in 1885 and 1888 show that a stone worthy of note was located about 200 metres north of the bridge.

- Two Hobbit settlements lie on the East-West Road between Bywater and the Brandywine, called Frogmorton and Whitfurrows. In the early twentieth century, there were two towns on Icknield Street between Birmingham and Bidford: Studley and Alcester. Studley has no obvious connection to Frogmorton, but nearby is Coughton Court, the seat of the Throckmorton family. The name Alcester is a conjunction of the Brittonic word for ‘white’ (from the local river) and the Latin word for a ‘fort’. Today, the only remaining evidence of the Roman fort is a few ridges or furrows, hence perhaps ‘Whitfurrows’.

The Shire road which Tolkien describes in greatest detail in The Lord of the Rings is not the East-West Road but one which runs parallel (to the south) and is narrow and winding in character [5]:

- Relative to the East-West Road, the position and orientation of the narrow road evokes the East Worcestershire Ridgeway. The E. Worcs. Ridgeway shares the alignment of Icknield Street (i.e. north-south) but lies two or more miles to the west.

- It is conceivable that Tolkien was inspired by G.B. Grundy’s essay on ‘The Ancient Highways and Tracks of Worcestershire and the Middle Severn Basin’, in which the E. Worcs. Ridgeway is described as ‘one of the most remarkable ridgeways in England’. Grundy’s essay was published in 1934-5, not long before Tolkien began writing The Lord of the Rings.

- Travelling towards the Brandywine from the west, the narrow road first ascends into the uplands known as Green Hill Country [6]. This terrain could be related to the Clent, Waseley and Lickey Hills, which Tolkien knew and loved from his time living in Rednal and from his stays at the cottage of his aunt’s family in Barnt Green.

- Beyond the Green Hills, the narrow road goes down into an arboraceous area called Woody End [7], just as the Ridgeway descends towards the medieval Feckenham Forest.

- The Woody End terminates in some unnamed hills which stand out into the lower land of the Brandywine valley. Between the hills and the river sits an inn called The Golden Perch, in the Hobbit village of Stock. The real village of Harvington, between the high ground of the Lenches and the River Avon, contains an old pub called The Golden Cross. Another word for cross is ‘rood’, which is also an archaic measurement of length. One fortieth of a rood is a ‘perch’.

The case for an official footpath

The likeness between the Shire and the West Midlands is very far from exact and many of the walkable lanes which Tolkien knew are now busy main roads. Nevertheless, there is considerable potential to create an official footpath which simultaneously explores aspects of the author’s biography and alludes to the flight of Frodo Baggins and his friends from the Black Riders in The Lord of the Rings, one of the best-known journeys in world fiction.

That expedition crosses the Brandywine River by ferry at Bucklebury [8], whence Frodo’s Brandybuck family originate. The E. Worcs. Ridgeway meets the Avon at the town of Evesham, where one of the oldest river ferries in England still operates. It transports pedestrians from Evesham to a village on the south bank called Hampton, where some of Tolkien’s maternal ancestors still dwelt during his mother’s lifetime.

My detailed argument for creating an official Tolkien footpath in the West Midlands is available to read as a pdf document here:

NEXT: ‘Why would Tolkien base the Shire on the West Midlands?‘